The Victorian era was one of supreme gentility. Manners and civility were the order of the day, and the essential elements of Western Decorum were observed in all settings, even, or possibly especially, in warfare. It was a time in which Britannic soldiers traveled great distances to preserve far-reaching satellites of the Empire, and order was commonly kept via the barrel of the Enfield. At this time the Empire found itself in a number of entanglements that required the reinforcement of scarlet-frocked Tommies. In 1850 a virulent discontent began to infect South Africa, and Queen Victoria found herself reigning over the Eighth Xhosa War, of which there would be nine. If you’ve never heard of these conflicts, it is forgivable, as they originally and most commonly were identified much less tactfully as the Kaffir wars.

The answer then, as ever, was to dispatch soldiers to help quiet the colonials. Soldiers mustered in Portsmouth, England to make for the South African coast forthwith. As a mark of the Victorian era, soldiers would not necessarily travel alone. Officers with wives and families were invited to bring them along for the adventure. Some soldiers marched aboard followed by their wives and children.

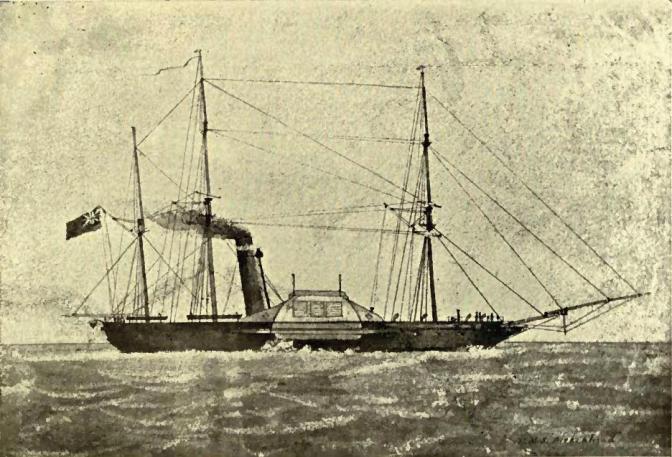

Once refitted and troops boarded, the ship Birkenhead made haste for the South African Cape. The Birkenhead was chosen because she was among the very fastest ships of the day. She was a ship with her metaphorical bow and stern in two separate eras. She was among the first iron-hulled ships, sailing quickly and predictably under power of steam. She also sported the large masts and hull design of a classic schooner.

— HMS Birkenhead at sail

The ship steamed south at the greatest possible speed so that the troops on board, representing ten separate regiments, might be deployed into battle at the soonest. The captain made every effort to trim time from the journey, and the ship made only a few stops along the way. At one interim stop in Simonstown, South Africa, nine light cavalry remounts were walked aboard with sufficient fodder to see them through the journey. When leaving port, the captain made a decision to trim travel time by skirting closely the African coastline. The ship made remarkable progress, pushing through calm waters at a rapid 8.5 knots. Though offering smooth sailing, the stillness of the ocean obscured dangerous rocks that lay just beneath the surface – rocks that would have otherwise been visible in a light chop.

At approximately 2am, the HMS Birkenhead struck one of those rocks and immediately took on water, flooding forward compartments instantaneously. At the moment of impact, there were approximately 640 souls on board, and many of them, quartered below decks, were drowned in their bunks. Those who could, struggled their way topside to make sense of the situation. The initial breech in the hull was likely a fatal one, though frantic subsequent maneuverings to extricate the ship resulted in additional breeches, condemning the vessel to a rapid end.

To further complicate matters, the emergency equipment onboard had long been neglected. Blocks, used to lower the lifeboats had been painted over to a frozen state. Ropes were rotted and snapped under use. The first lifeboat to launch swamped and immediately foundered. Everyone on board knew within moments that the ship was doomed and that escape or rescue would be limited. In the dark of night, with too few available life rafts, and the decks of the ship already slipping beneath the surface of the water, officers on board made a hasty, yet chivalrous decision. It was at that terrible moment that a new element of etiquette was formally expressed. Priority was offered to the women and children on board, and they, first, occupied the precious little space aboard the lifeboats that could still be launched. Women and children first.

— soldiers at attention

To ensure this would be a matter beyond discussion, the yet-surviving soldiers gathered in sharp order upon the deck and stood at rigid attention. They were still, none said a word or emoted. They were resigned and adamantine in their final mission of self-sacrifice. The innocents were loaded into the few lifeboats and shoved-off safely while the soldiers stood fast, allowing the lifeboats to escape peacefully without danger of being overloaded and swamping. The water approaching the soldiers’ feet and the ship began to break apart all around them. With one last act of charity, a few soldiers cut loose the horses from their leads, and pushed them into the sea with a meager hope that they might make their way to shore. As the lifeboats paddled away from the crumbling ship, the horses splashed and swam vigorously into the darkness. With little hope, though elevated chins, the soldiers waited patiently and quietly for the water to reach their boots and beyond.

Once in the water, those who could swim did. Many more drowned within the immediate vicinity of the wreck. Some clung to bits of floating debris. Sharks took a toll on those who thrashed for survival. A few men swam successfully the two miles to shore. Eight of the nine cavalry horses were eventually found alive on the beach.

The legacy of the Birkenhead tragedy was, for a time, a metaphor for finding within oneself the ability to be noble, and do one’s best in a hopeless situation. The story of The Birkenhead Drill foreshadows what we all will face, somehow and eventually, and reminds us that when it is our time, we can yet choose to have our chin up. Hemingway was obsessed with the idea of grace under pressure and finished most of stories with a crushing, yet dignified defeat of his protagonists. Shakespeare offered the perspective that hopeless situations offer a great share of honour. Alfred, Lord Tennyson reminded us that ours is not to wonder why. But what is the point of such sacrifices?

The pregnant words – women and children first – have become the enduring element of the story. And with that, it is possible that the moral has become obscured. Maybe clarity can be found elsewhere.

Many years later, in 2014, another ship was to meet a similar fate as that of the Birkenhead. The ferry ship Sewol left port at Incheon, South Korea, with several hundred passengers, mostly high school students, on a field trip adventure. Like the Birkenhead, the Sewol was traveling at a relatively rapid pace for the day – about 20 knots. And similar to the Birkenhead, a navigational blunder resulted in catastrophe. For reasons still not entirely clear, the ship’s crew made a sudden and extreme turn, which caused the ship to list heavily to the port side. Overloaded and unsecured cargo tumbled and crashed to port, sending it further off-balance, eventually listing to a point of no return. Water flooded below decks immediately. The crew on the bridge, stunned, tried desperately to make sense of the situation. The engines had stopped. The power went out. In only a few moments, the ship’s fate was obviously hopeless.

Unlike the Birkenhead, officers of the ship provided no order to the ensuing chaos. The only message to passengers went briefly over the PA – go to your room and stay put – an order that would doom those who obeyed. As the passengers huddled in their tilting and flooding cabins, the ship’s captain and several accompanying crew-members saw to their own safety. The captain was the very first to evacuate; no evacuation order ever reached the passengers.

One crew-member did make a quick and accurate appraisal of the situation and acted immediately to help others. She was not a member of the senior crew, nor was she ever present on the ship’s bridge. She wasn’t even a full-time employee. She was a twenty-two year old member of the commissary staff who’d, up to that moment, been serving breakfast to passengers. As soon as the ship listed, she knew something was terribly wrong. Without hesitation, she began urging passengers to the upper-decks where they would be most safe. She personally led several people to safety, and then turned around to make several trips back below decks to gather life jackets. She delivering armloads of them to the frightened high-schoolers who awaited rescue. There was a shortage, so she did not take one herself. Concerned and grateful students asked her why she didn’t wear a life-jacket, and her reply was simple and dutiful – the crew would not evacuate until all passengers first were safe.

The ship continued to founder, and quickly. With most of the people still below decks, the Korean Coast Guard had little time to reach them. It was apparent that not everyone, not even most would be saved. Crew-member Park Jee Young, was last seen alive within a hallway of the ship, chest high in water, helping passengers by physically pushing them toward one of the few accessible openings to safety. Later her body was recovered without one of those precious few life-jackets.

* * * * *

To take your chance in the thick of a rush, with firing all about,

Is nothing so bad when you’ve cover to ‘and, an’ leave an’ likin’ to shout;

But to stand an’ be still to the Birken’ead drill is a damn tough bullet to chew,

An’ they done it, the Jollies — ‘Er Majesty’s Jollies — soldier an’ sailor too!

Their work was done when it ‘adn’t begun; they was younger nor me an’ you;

Their choice it was plain between drownin’ in ‘eaps an’ bein’ mopped by the screw,

So they stood an’ was still to the Birken’ead drill, soldier an’ sailor too

~ Rudyard Kipling