It is important for a modern gentleman to establish at least one exemplar in his life, someone to whom he can look for inspiration, direction, ideas. An exemplar’s life need not be perfect—none will be if you look closely enough. In fact, one of the comforts of having an exemplar is being aware of that person’s mistakes.

I do not have a single exemplar, but rather a collection, all for different reasons. Some are more important than others. It is helpful I think, to have exemplars in one’s back pocket to draw out when life presents a unique challenge. When hosting a dinner party and the roast hits the floor, I wonder, what would Julia Child do? When lost in the wilderness and discomforted by the climate, I wonder, what would Matthew Henson do? And so forth.

An exemplar need not be famous. This person can be familiar and personal, or ancient and obscure. An exemplar need only have a great personality. Every great personality is earned, frequently during a moment in one’s life that is transformational, the moment in which that person leaves the demesne of the common and becomes exceptional. It is not enough to be brilliant, or beautiful, or witty. It is also not enough to simply be in the right place at the right time. A person’s natural gift must be coupled with an extraordinary moment that is enlightening.

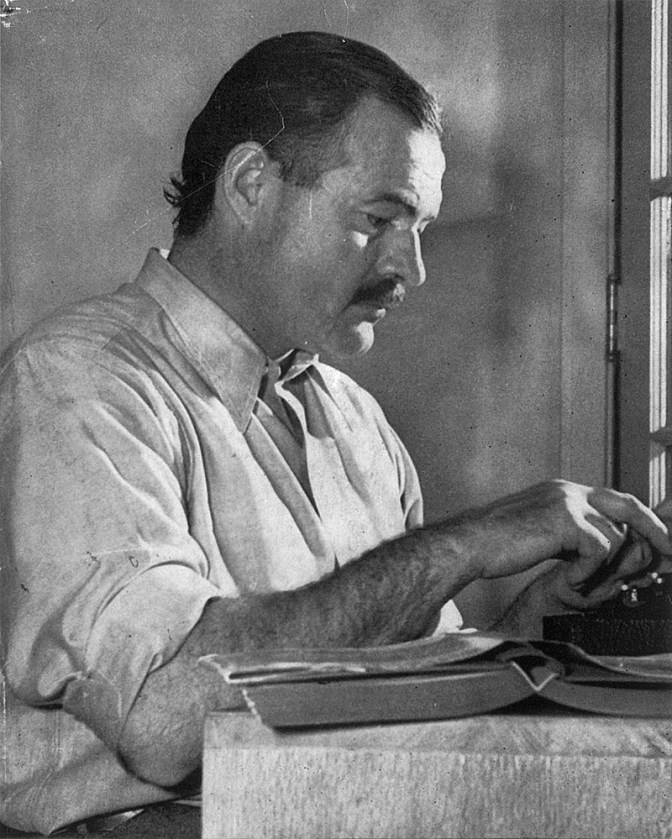

At the age of 18, Ernest Hemingway—a brave but common personality—signed up to drive ambulances in the world war in Europe. He traveled to the Isonzo Front in 1918, where the allied Italian army was fighting the ancient and decrepit Austro-Hungarian Empire. The war was fought along the peaks and ridges of the Julian Alps. Every bit the stalemate of the Western Front, these poor souls lived in trenches that smelled like sewers, where the monotony of picking lice and scrounging for the rare morsel of food was broken by moments shooting, explosions, and pain. Only these trenches were dug high in the alpine tundra, exposed to the snow, wind, lightning. The discomfort was unimaginable to anyone who did not live it. There, Hemingway met this pain early in his service when he was struck and severely wounded by shrapnel. He spent the rest of his service in the care of a military hospital.

Like many injured soldiers, Hemingway became enamored of the pretty and gregarious nurse who attended to his wounds. Unlike most soldiers, his affections were returned and they fell in love. Although she was seven years older than he, they made plans to marry after the war.

In the end, it was not the battle that broke Hemingway. It wasn’t the shrapnel that tore his flesh, nor was it the diabolical violence that he witnessed in the trenches high in the Slovenian mountains. It was the wound to his heart. Agnes eventually outgrew young Ernest and found new love with a dashing Italian officer. After Ernest returned to the US, she wrote him a letter of the news: I am writing this late at night after a long think by myself, & I am afraid it is going to hurt you, but, I’m sure it won’t harm you permanently. She may have been incorrect in her final estimation.

Ernest Hemingway is, of course, an exemplar of mine. Recently I made it my mission to explore the Julian Alps, the place where he found his extraordinary moment and became a great personality. This adventure was a pilgrimage for me. And on this pilgrimage, I traveled by whitewater raft, by horse, and by canyoning, a mode of transport that was wholly new to me.

* * * * *

For further reading on Hemingway’s experiences in Slovenia, I recommend: A Farewell To Arms