Grand Touring

~It is difficult to imagine scaling a peak in such clothing.

Part I

There is nothing specifically English about travel and exploration. However, the English have always taken to travel with a certain style that is unique to their sensibilities. A stoic, furrowed brow, stiff upper lip, and the toting of an umbrella is the way in which we often think of English explorations—or incursions, depending on one’s point of view. Of course it is true that a good deal of English travel has included red-coated, pith-helmeted soldier types who claim foreign territories by the barrel of an Enfield and the stripes of the Union Jack. However, it has not always been this way. During the Victorian and Edwardian eras, English civilian explorers set out in great numbers to see and explore the world. Numerous clubs–like the Royal Geographic Society–sponsored cultural and scientific explorations for the sake of a greater understanding of humanity and our natural world.

Victorian England witnessed the new economy of industrialization. Industrialization brought leisure time and discretionary spending to a new and growing middle class. And for that middle class, seeing the world became all the rage. It was an age when explorers boarded huffing steam trains with the help of porters who hefted aboard steamer trunks full formal wear. Men wore day-cravats and top hats while cantering gangly camels through Giza to the foot of the Great Pyramid. Women wore bodices and petticoats and dragged sunshade umbrellas behind them as they climbed to the tops of Alpine mountain peaks.

Though the attire and equipment had not yet evolved to designs that were appropriate for the more challenging altitudes and latitudes of outdoor travel, explorers pushed on undaunted.

The purpose was simply to explore and learn for the sake of understanding people and the natural world. Field research studies had not yet become the domain of professional or university scientists. Expeditions like the excavation of Egyptian burial sites, the categorizing of Galapagos finches, and the cartographic exploration of Himalayan peaks were all done by amateur explorers.

Over the next few weeks I will consider and share with you the contributions of men and women Victorian explorers who ventured very far afield to make contact with distant cultures, or uncover the buried ruins of past civilizations, or document new and important species.

Charles Darwin

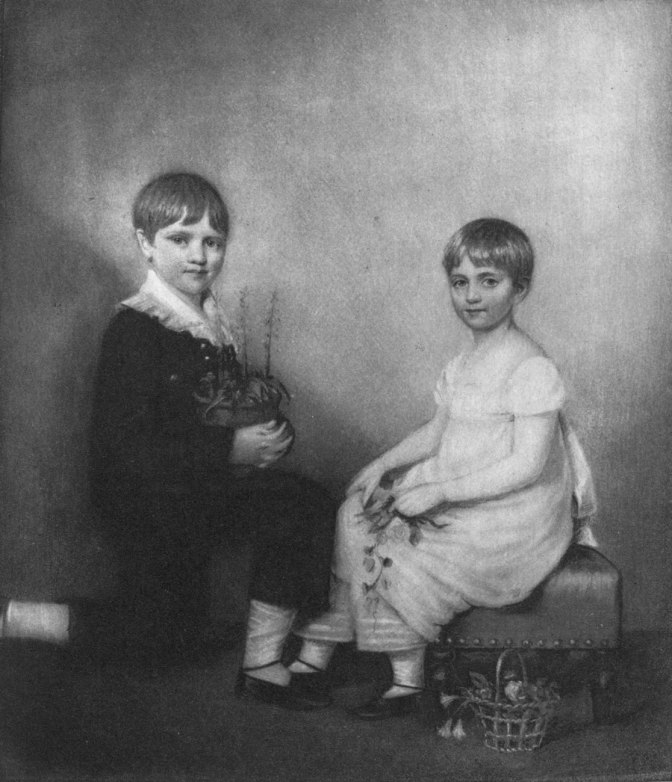

During the cold winter of 1809, a boy was born into a large and wealthy family in the English town of Shrewsbury. He was the fifth child in a family that would have six. It was a well-off family, and his mother and father both held the sort of surnames that established him a future, if not automatic access to society even before his birth.

The boy’s father was a medical doctor who had a mind for research and investigation. He took a particular interest in understanding the workings of the human eye and made important discoveries. His mother’s family, the Wedgewoods, made their mark on the decorative arts world with their distinctive pottery.

The boy’s father, Robert, had fairly grand expectations for his son Charles. He encouraged him to seek academic challenges and provided him with every opportunity to grow as a student—none of which Charles earned or took advantage of. In fact, Charles was a rather uninspired student whose greatest academic talent was to work just hard enough. Instead of his nose in a book, Charles preferred his fanny in a saddle and spent as much time as possible galloping about–astride his favorite horse. The rest of his time was spent shooting, and I cannot say there is evidence he did not pursue both of these passions at the same time.

~Charles never did give up his passion for riding.

Like many fathers who want the best for their sons but can find no avenue to inspire them, he pushed Charles towards his own métier. At the age of 16, Charles spent a summer following his father to medical calls in which Robert treated needy patients. During these outings of lancing boils, mitigating tuberculosis, and cleaning wounds, Charles learned the rudimentary skills of doctoring–an experience that would be classified as a medical apprenticeship. This experience (and his father’s connections) allowed him entry the medical school at the University of Edinburgh.

Charles did not share his father’s focus, nor did he have his interest in the medical sciences. In fact, he found the university lectures incredibly dull, and frequently skipped classes to be outside and explore the natural environs. The practical presentations of medical school, particularly human dissections and surgeries, were far too unsettling and left him an emotional wreck afterward. Charles began to avoid school in general and found solace in the friendship of a new found comrade named John Edmonstone. John was an accomplished taxidermist who shared with Charles all that he knew about animal biology. The many years of applying his craft made John a keen observer of the adaptations animals made to their habitat, and he discussed this frequently with Charles. The friendship would not have been so odd, had it not been for the fact that John was a recently freed African slave who had no connection to English society and no history English academia. Charles was the sort of gentleman who took no notice of this sort of detail, however. Charles and John spent so much time exploring and discussing the animal kingdom that his grades slid to unrecoverable depths. Despite his respect for his father, and his well-meaning effort, it became clear that Charles was not to be a doctor, and left the university.

By this time, Robert was exasperated. He had no other ideas for his son besides suggesting (this time, more forcefully) that he go to school (this time, Cambridge University) to become an Anglican priest. In retrospect, the suggestion seems more punitive than productive as neither Robert, nor any of his family belonged to the Anglican Church. They were Unitarians with only the mildest connections to the national religion.

In possibly the greatest example of historical irony, Charles thrived in his religious studies. In fact, not only did he thrive, he was a student of some distinction—number 10 in a class of 178. During his studies, the text that inspired and excited Charles most was Natural Theology, a book that presented evidence for a divine and intelligent hand in the design of the natural world. To him, this idea seemed plausible.

Beyond his official class-work, Charles threw himself wholly into university life. He participated in clubs and societies. He carried on his passion for animal identification—learned by John Edmonstone—and participated vigorously in the school’s entomology club. Specifically, Charles had a passion for collecting and organizing beetles. He seemed gifted at collecting specimens and finding the differences and similarities between the innumerable beetles that he caught and categorized. Fellow club members noticed his talent, and he became a luminary among amateur naturalists. He was a natural at observing and inductively making sense of the natural environment and earned—this time—a spot on a geologic expedition to Wales. On this trip, Charles proved himself to be capable and competent as a field researcher and contributed a great deal to the success of the mission of the expedition. When Charles arrived home from his geographical work in Wales, he found a letter waiting for him that would change his life forever. More importantly, it would help change the world in ways that were, at that time, unimaginable.

The letter offered a spot on an expedition—an expedition larger and more involved than he ever imagined. The entire trip was to spend at least two years exploring and charting the coast of South America. He was asked to join less for his skills in ecology, which were exceedingly amateurish, but rather for his social stature as a gentleman, which was unfinished but promising—if only because of his family’s name. In short, he was to be the company of the ship’s captain, who would otherwise be surrounded by naval rogues and boring academics.

When Charles told his father, Robert rejected the idea out-of-hand. A waste of time, he insisted. No applicable use, he assured. He couldn’t allow it. A family member stepped in and pleaded on behalf of Charles.

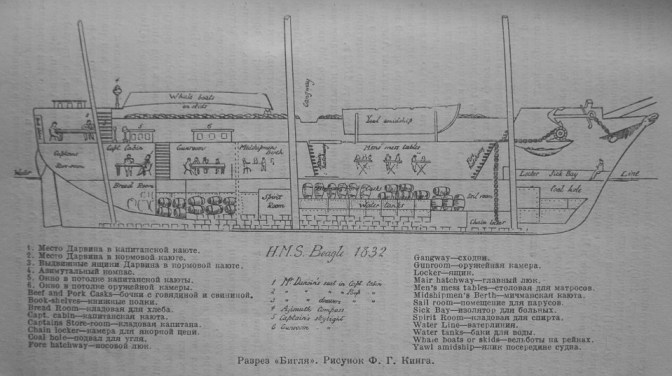

Robert eventually relented and Charles packed his bags. He reported on-board the ship that was to become his new floating home. The HMS Beagle was not a large ship, but it had the large mission to sail across the world. Charles Darwin could not be more pleased.

Part II

“Capt. F. wants a man (I understand) more as a companion than a mere collector & would not take any one however good a Naturalist who was not recommended to him likewise as a gentleman. … there never was a finer chance for a man of zeal & spirit… Don’t put on any modest doubts or fears about your disqualifications for I assure you I think you are the very man they are in search of.”

~Letter to Charles Darwin concerning his invitation to sail aboard Beagle.

Charles Darwin was set to sail on the most exciting scientific expedition in history. He was offered the trip of a lifetime not because he excelled in studying ecology (though he did), but rather because of his status as a gentleman. The captain of the HMS Beagle, Robert FizRoy, was concerned about his likely loneliness during the duration of the long voyage and sought the friendship of a suitable gentleman—and so it was Darwin’s pedigree, not degree, that made him eligible. It would seem that Victorian gentlemen, unlike Modern Gentleman, are born and not made. Nevertheless, Darwin decided to make the best of his opportunity.

The mission of the Beagle was to survey and chart the coasts of southern South America. Specifically, they were to make note of land features as observed from the sea for the purpose of naval and commercial navigation. At that time, important intercontinental shipping routes were only just being established. Darwin looked forward to moving beyond his role as an gentleman and naturalist.

Darwin confined himself to his room for much of his time at sea, where he could scribble in his journals during periods of quiet waters. In fact, during his self imposed isolation, Darwin filled dozens of journals with thoughts and observations—a practice that became his life-long habit.

When the Beagle first landed, a relieved Darwin set foot on land. He finally felt freed and unencumbered by the social and nautical uneasiness aboard the Beagle. Before him was the South American continent. It was completely new to him, and it contained ecological wonders that were yet mostly unknown to people back home in England. He did not want back aboard the Beagle, at least not to spend anymore time than absolutely necessary. FitzRoy and Darwin agreed that Darwin should explore and make his way cross-country by any means he could find and check-in with the Beagle at prearranged ports.

While Darwin was becoming a more serious and studious gentleman of science, old habits would be impossible to shake. At every opportunity, he sought the transportation of a speedy mount, and with his firearms, he traveled far inland where he spent his time riding and shooting throughout the campo. This time, rather than failing grades, his passions earned him one of the most important collections of plants and animals made by a field ecologist. At each meeting with the Beagle, he carefully crated his findings—along with many volumes of annotated journals—and prepared them for shipment back to England.

Darwin explored jungles and rivers, arid plains, steep mountains and encountered people of cultures never contacted by Europeans. He collected plants and preserved animal specimens. He created cartographic maps and charts. He made meteorological observations. He recorded languages unknown to English ethnographers. There hardly a scientific discipline he did not explore on this expedition.

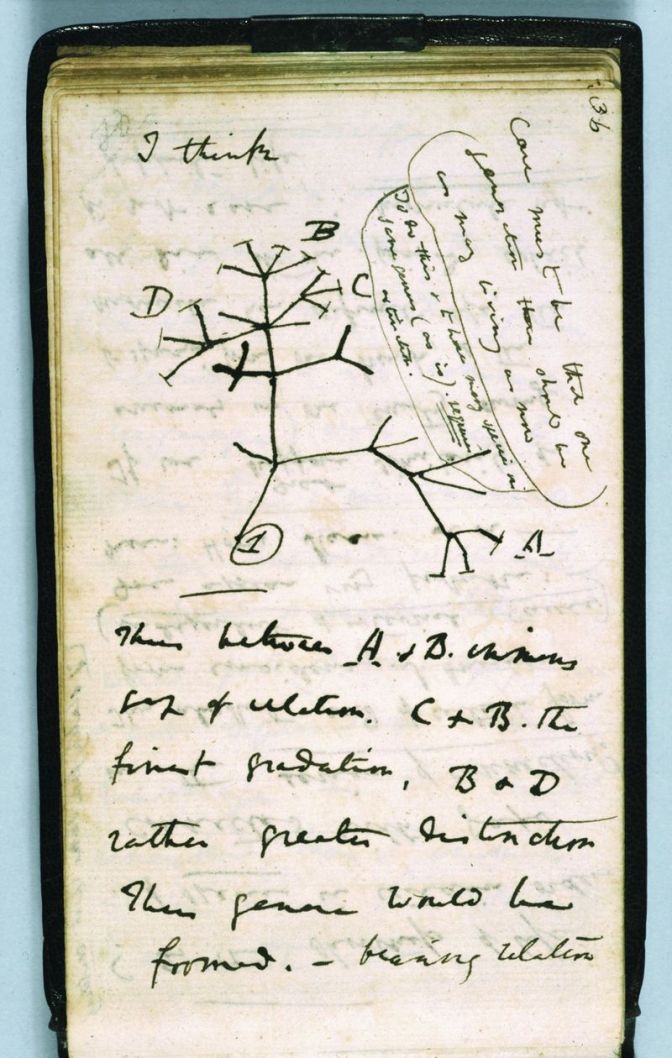

Darwin spent significant time wandering about the different Islands of the Galapagos, which are off the coast of what is today Ecuador. He was particularly taken with the finches that lived there. He noticed that from island-to-island, the finches had different appearances—especially their beaks. He noticed also that the beaks were suited for the food supply of each island, which tended to vary a great deal. On islands where nuts and seeds were prevalent, the finches tended to have larger, sturdier beaks. On islands with more available insects, finches had more slender beaks for probing and snatching bugs. His observations of these finches seemed significant to him at the time, and he was careful to crate many specimens to be sent back to England.

Unfortunately riding and shooting were not the only boyhood habits that Darwin could not shake. He was still, and always would be a disorganized person. When Charles Darwin got back to England to sift through his crates of notes and collected specimens, he found his work a shambles. He neglected to label or even group the many things that he collected in the field. In fact, it took years and the help of some of his fellow Beagle compatriots to make sense of the contents of these crates. But he never gave up, and eventually he created a model that explained the finches that he observed on the Galapagos Islands. It was his theory that the finches underwent a gradual process of adaptation to take advantage of each island’s food supply, and that each finch was selected naturally for its environment. It took many more years to write the book that explained that model. During that time, I wonder if Charles’ father ever forgave him for all of that horseback riding, shooting, and globe-trotting.

A Stark Reality

On her ninth birthday, a sickly homebound child received a gift that would chart the course for the rest of her life. It was a very large book that was—by all measures—not a children’s book. But, unlike most children, she loved to read, and did so voraciously and particularly enjoyed stories that let her explore beyond the confines of her home. Most children her age preferred to play outside and explore creeks and rivers and capture frogs and insects. She could not do those things. Because of her frailty, reading was the only chance at adventure that she had. On the cover was a title that had established a myth of the East, maybe the myth of the East. Beyond the cover were stories of sorcerers and magic lamps, bands of rogue thieves, and sailors who visited mythical lands. At the heart of the book was the story of a man who was responsible for astonishing brutality and heartache, unforgivable hubris, bloodshed, and agony. It was also a story about a woman’s cleverness in survival. The young girl could not wait to pore through her new treasure One Thousand and One Nights. Freya lost herself in the reading of adventures.

Unfortunately, the book only offered her adventures of the mind. As she slowly grew out of her childhood sickliness, she experienced a terrible accident in which her hair became entangled in a factory machine, disfiguring slightly her face and further relegating her to the confines of her family’s home. Freya’s childhood was difficult and lonesome. But Freya continued to read of adventures.

Freya entered into young adulthood in pursuit of marriage and the stability of family life and homemaking. She fell in love with an Italian doctor and became engaged. The engagement did not last, and the doctor left with her with a broken heart. And Freya continued to read of adventures.

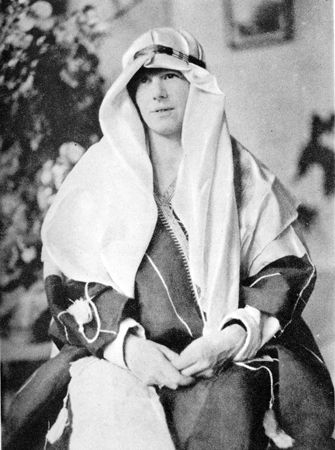

More than anything else, Freya continued to read the book that originally sparked her interest in distant lands and exotic cultures. Except now, the stories within One Thousand and One Nights seemed not as distant, almost accessible. Home seemed to have little appeal for her and she became restless. At the age of 33, Freya Stark left her home and her lonely, common life for Lebanon. She would never look back.

Freya had a gift for reading and language and threw herself into learning Arabic. She also became enamored of the many cultures that she found there. However, it was not enough for her to merely live in the Middle East, she wanted to explore and see places that no other European had ever seen. Freya dedicated herself to exploring the most remote possible areas of the Middle East. It would be a journey every bit as epic as One Thousand and One Nights. She traveled by sputtering car, loping camel, and stagger-stepped mule. She clambered up mountains, and plodded across deserts. She made contact with secret religious societies and studied sacred holy books. Her greatest feat during this journey was reaching the fabled valley that was once the home of the Cult of the Assassins.

Freya Stark spent the rest of her life exploring and writing about the Middle East. I recommend her first book The Valleys of the Assassins: and Other Persian Travels.

You Call This Archaeology?

Date: 1906

Location: Somewhere on the Bolivian-Brazilian border

A shaggy, bearded gentleman pushes and fights his way through thick jungle vegetation. He gains only half-steps before having to hack and cut with a machete at the green wall of leaves and vines before him. His heavy khaki shirt is soaked with the sweat of work and tropical humidity. He wears also a pair of loose fitting dark breeches held up by a heavy utility belt, tall brown riding boots, and a hat–always the hat. He never seems to go anywhere without it. It is large and peaked, with a full brim. It protects him from the sun, keeps the sweat from his eyes, but most importantly, gives him a rakish appearance when worn cocked to one side.

Behind him is a small army of locals who are there to help him. Some are porters, hefting baggage and crates on their backs. Others follow more closely. They are his guides who know the jungle. They show him the way and see to his safety. These locals see him as more than a client. Unlike most Europeans, he speaks with them and not at them. He is thoughtful and aware of each person who travels with him. He pays them well because he respects them, and gives them gifts because he likes them. The loyalty that this adventurer enjoys is not purchased, however. Percy Fawcett is charming and genuine, personable, and every bit the swashbuckler.

As the expedition pushes ahead, slowly and deliberately, the group becomes suddenly stunned–and then everyone is sent into a panic. An enormous anaconda—sixty-two feet by Fawcett’s estimation—is slithering towards him. It is a man-eater. It means to kill him or someone near him. Fear takes hold of his crowd—shouts, scrambling, dropping of boxes. Fawcett stays put and coolly reaches for his holster, draws his pistol, and dispatches the interloper with hardly a shrug. He calmly turns to see and make sense of the pandemonium that has developed behind him.

* * *

Shooting this snake would actually become one of his greatest misadventures. When he returned to England from his expedition, he reported to the Royal Geographic Society—the ones who paid for his expedition. When standing before the committee who was responsible for him, he relayed this moment of the trip. The tuxedoed members of the society became incensed–furious, in fact. One can imagine their stuffy annoyance: “My god, Fawcett, you mean to say you really shot it?! A sixty-two foot specimen, and you just shot it!” Of course he did. And they could only ask such a question from the safety of their offices. But they wanted it for a collection, and his bullet had spoiled it.

Besides, Percy Fawcett had not been sent to South America to collect specimens of plants or animals. He was an archaeologist and sometimes cartographer. He had been sent to South America to help settle a disputed territory and its borders. His stock in trade was the cultural history and homelands of South American tribe’s people.

Percy Fawcett was sent on this mission because he was an expert of the territory. He had made several extended expeditions to the interior of the South American continent over his lifetime. It was not infrequent for him to make contact with people who had never before seen a European. He specialized in learning customs and languages. He made friends easily, and locals looked out for him.

~Percy Fawcett, a proper gentleman, was comfortable in the saddle of a horse.

His knack for adventure was, by all measures, impressive. Possibly he pushed himself because he had very large shoes to fill. Percy’s father was born and raised in India, a world adventurer, and a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society. His brother was a famous mountain climber and adventure writer. To get a word in at a family dinner-table such as this, one must have something exceptional to contribute.

As an archaeologist and historian of South American cultures, Percy Fawcett learned of many local legends and myths. Among these, he learned of a supposed lost city in the uncharted territories of Western Brazil. There was little known about the city, not even a name. In fact, when he began pitching a new expedition to prospective financiers, he was forced to call this lost city simply “Z.” His experience, his connections to the Royal Geographic Society (if sometimes strained), and his engaging personality earned him a fully-funded expedition to seek out “Z.”

In 1925, Fawcett’s expedition broke through the dense exterior of the Brazilian jungle, and he was never heard from again. No one knows exactly what happened to him. Some think that an aggressive tribe killed him and his party. Others believed that he established a commune in the jungle and never intended or expected to return to England. Most likely, he and his companions perished from jungle disease. No one will ever know for sure. However, his life and persona have lived on to inspire a similar though fictional adventurer. My guess is, at some point during this contribution, the theme song of this character has reverberated in your head.